Crisis Budgeting Tools and Trends

Crises can create significant challenges for PFM performance. This chapter discusses how countries respond to crises from a PFM perspective. Also, the PEFA framework is leveraged to describe the impacts of crises on PFM performance. Finally, the chapter describes general trends in how governments have used PFM as a strategic tool to meet the fiscal demands of crises.

Disruption, Loss and Pressure

Crises come in many forms, often without warning. A crisis generally refers to a low-probability unexpected event with significant consequences that call for immediate and decisive responses (Durst, Acuache, and Gerstlberger 2022). Crises typically have three common elements: surprise, threat, and short response time. They differ in the human and financial losses, duration, and who or what is responsible. The overall impact is affected by the state of the economy, social conditions, and the government’s response. For the COVID-19 pandemic, the World Bank estimates that global GDP contracted by 3.4% in 2020, the deepest global recession in more than 80 years (Global Economic Prospects 2022).

Crisis Sources:

examples

Floods, hurricanes, tornadoes, volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, tsunamis, storms and other geologic processes

impact

Loss of life and property damage

duration

Short

responsible

Natural processes of the Earth. The frequency and severity of natural disasters are likely to increase over time because of climate change.

Examples

Financial crisis, economic recession

Impact

Unemployment, poverty, decrease in living standards

Duration

Varies

Responsible

Humans

Examples

Global pandemics

Impact

Loss of life, downfall in economic activity

Duration

Typically 12-24 months

Responsible

Natural pathogens

Examples

War, insurrection

Impact

Loss of life and property damage

Duration

Varies

Responsible

Humans

Crises place extraordinary stress on countries’ PFM systems.

With high uncertainty and changing circumstances, budgeting becomes a continuous reactive process that strains existing procedures, assumptions, and timelines.

PFM Outcomes and Responses in Crisis Situations

| Desirable PFM outcomes | Normal circumstances | Crisis context | PFM response |

|---|---|---|---|

Aggregate fiscal discipline | Aggregate expenditures and deficits are consistent with a sustainable macro-economic framework and level of debt. | Reduced revenues and unanticipated expenditures may increase deficits. | Risk management provides for risk retention and risk transfer mechanisms to accommodate additional financing needs. |

Strategic allocation of resources | Public funds are applied in support of the government’s development policy objectives. | Resources may have to be reallocated from development policies to disaster response and recovery. | Resilient systems anticipate the potential need for disaster response and allow flexibility to reallocate resources. |

Efficient service delivery | Outputs are delivered at the lowest cost. Value for money considerations encompass costs to society as well as to the public sector. | Supply disruptions may hinder and increase the cost of the delivery of public services and the recovery of assets. | Planning and expedited procedures help mitigate the risk of supply disruptions and sudden price spikes. |

Timeliness | Public funds are executed expeditiously following standard operating procedures. | Government must respond to immediate threats to persons and property during disaster response and restore economic activity during recovery. | Government uses expedited operating procedures to meet disaster response and recovery needs. |

Effectiveness | Public funds are applied in a manner that successfully achieves the intended outcome. | Government priorities shift towards crisis response and recovery. | Budget and procurement systems adapt to new policy priorities and facilitate the achievement of crisis response and recovery goals. |

Transparency & Accountability | Public funds are applied transparently for the intended purposes, with reliable systems of internal and external control. | Expedited procedures may lead to a relaxation of controls, increasing the risks of waste and abuse, and may hinder reporting. | Control systems anticipate the need for not only expedited expenditure, but also audits, and retain the ability to track and report on expenditure ex-post. |

Equity | Public funds are allocated fairly, in a manner that is inclusive of all social groups and takes account of their needs. | Needs may be unevenly weighted towards some segments of the population on a temporary basis. | Government identifies and targets adversely affected populations and responds to their needs. |

Source: World Bank, 2022

“With regard to the 2009/10 budget, the Budget Call Circular had yet to be distributed to MDAs by end November 2008. This was due to delays in getting resource availability estimates from the development partners in the current global economic crisis. This could impact the budget preparation timetable”

-Uganda

Learn more:

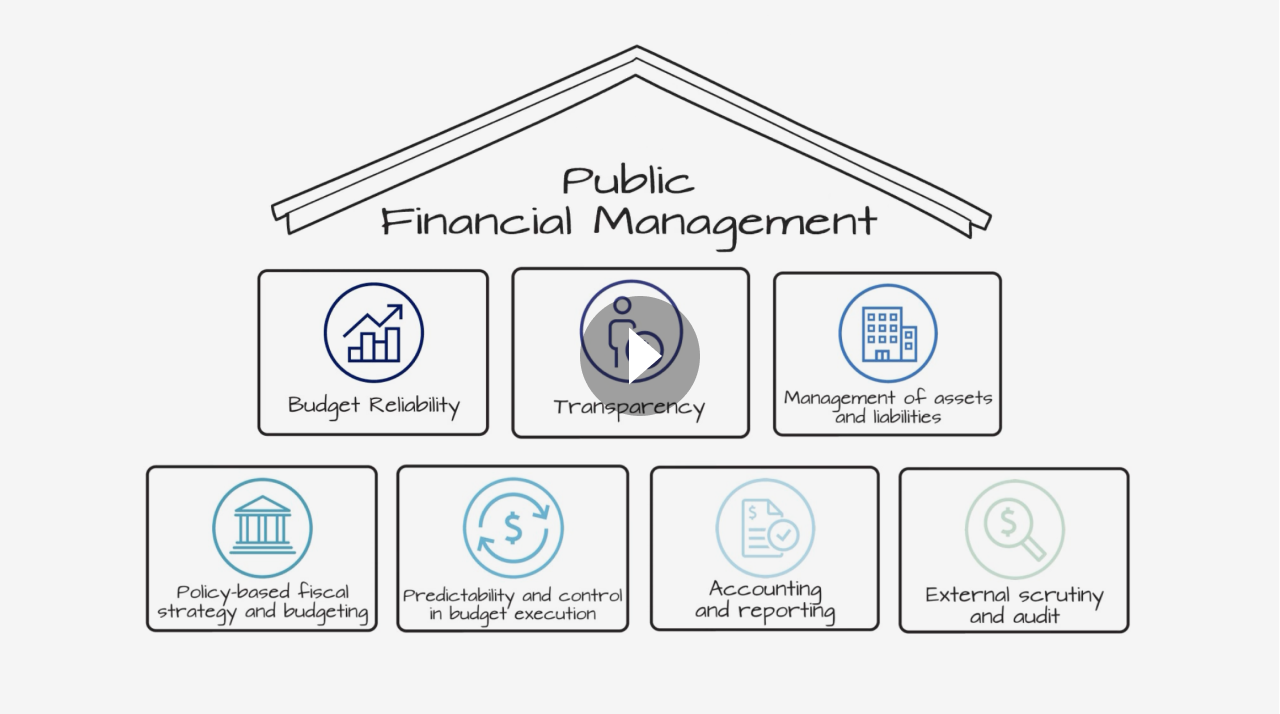

How does a crisis affect each PEFA pillar?

| Pillar | Description | Possible Impact |

|---|---|---|

I. Budget Reliability | Expenditure outturn | Expenditure deviations increase. |

Expenditure composition | Changes in demand for goods, services, and transfers. Pressure to use contingency funds increases. Pressure to take on new debt increases. | |

Revenue outturn | Domestic revenues from taxes, fees, and other sources decrease. Revenues from grants and donations increase. | |

II. Transparency of Public Finances | Central government operations outside financial reports | Operations outside the budget may increase. |

Performance information for service delivery | Performance information systems may not be established for crisis measures. | |

Public access to fiscal information | The urgency to act may delay the publication of public information. | |

III. Management of Assets & Liabilities | Public investment management | Ad hoc adjustments to public investments increase. Quality of economic analysis decreases. |

Public asset management | Financial asset prices decline. The ability to monitor non-financial assets also declines. | |

Debt management | Approvals of debt and guarantees increase. There is increased difficulty in implementing debt management strategies. | |

IV. Policy-Based Fiscal Strategy & Budgeting | Macroeconomic and fiscal forecasting | Underlying macro-fiscal projections change. |

Fiscal strategy | There is increased pressure to reprioritize the fiscal strategy. The credibility of fiscal forecasts deteriorates. | |

Medium term perspective in expenditure budgeting | There is increased pressure to deviate from annual and medium-term expenditure ceilings. | |

Budget preparation process | There is increased pressure to adjust budget preparation procedures. | |

Legislative scrutiny of budgets | Rules limiting the executive’s discretion to present amendments to budget appropriations are circumvented. | |

V. Predictability & Control in Budget Execution | Revenue administration | Stock of revenue arrears increases. The likelihood of delays in receiving, reconciling, and reporting revenue data also increases. |

Predictability of in-year resource allocation | Cash forecasting becomes more challenging. There is increased pressure for multiple in-year budget adjustments. | |

Expenditure arrears | Stock of expenditure arrears increases. There is an increased risk of arrears not being captured in the Financial Management Information System (FMIS). | |

Procurement | Procurement methods are altered to accelerate acquisitions. The number of contracts awarded through non-competitive methods increases. There is an increased risk of corruption in the procurement of emergency supplies and services. | |

Internal controls on non-salary expenditure | Expenditure commitment controls decrease. Exceptions to payment rules and procedures increase. Internal controls are modified/diluted, leading to an increased risk of corruption, fraud, wastage, and inefficiency. | |

Internal Audit | Internal Audit is called upon to play a more significant role in compensating for modified controls. | |

VI. Accounting & Reporting | In-year budget reports | There are delays in producing budget execution reports. |

Financial Data Integrity | Risks to the integrity of financial data could develop. The ability to capture crisis-specific expenditure could be challenged. | |

Annual financial reports | There are delays in producing annual financial statements. There is incomplete picture of fiscal accounts. There is an increased risk of non-compliance with accounting standards. | |

VII. External Scrutiny & Audit | External Audit | Audit plans and programs prepared prior to the crisis will need substantial revision. Responses to audit inquiries are delayed. The independence of Supreme Audit Institutions could be under stress. |

Legislative scrutiny of audit reports | Submissions of audit reports on budget execution to the legislature are delayed. The legislature review of audit reports may not be timely or effective. |

Impact of Crisis on Expenditure Outturn

“The onset of the global financial crisis … forced the government to relax its fiscal stance.”

- Philippines

Note: The chart was constructed using data from an unbalanced panel of 156 countries over 15 years, from 2007 to 2021. | Source: WB Data Portal and the UN website: SDG Indicators Database.

Stakeholder Analysis during a Crisis

Key Insights

“Government revenues were reduced in 2009-10, partially as a result of the global financial crisis which led to a material reduction in expenditure compared with budget forecasts.”

- Nauru

54

%

“…is the average year-over-year increase in absolute budget deviations between 2019 and 2020 when the COVID-19 crisis emerged”

Significant overspending occurs at the aggregate level when there is a crisis (e.g., the Global Financial Crisis in 2008 and the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020).

71

%

"...of surveyed countries reported deviations in expenditure outturn that exceeded ± 5% in 2020 at the onset of COVID-19"

“The impact of the global recession on Tanzania reduced collections, which fell 10% short of budget. The PEFA score for PI-3 (Aggregate revenue out-turn compared to original approved budget) deteriorated from “A” in 2005 to “C” in 2009”

-Tanzania

Fewer countries were able to maintain credible budgets in 2020 when compared to 2019. Of the 77 countries that provided data for FY2020, about 57 (or 71.25%) reported budget deviations larger than +/- 5%. This implies that the COVID-19 pandemic significantly altered priorities. Approximately 47.5% (or 38 countries) overspent their budgets while the remaining 42 countries underspent.

When a crisis strikes, it affects everyone, including important government institutions who are under significant pressure to make quick decisions to safeguard lives and livelihoods. The urgency to act can change existing roles and responsibilities, and challenges a range of stakeholders to devise and implement the crisis response.

PFM in Crisis Management

Crisis management is a critical government function that requires planning and executing a response to a crisis as it unfolds, often in unpredictable ways. PFM is crucial for this objective and plays an integral role in each of the three broad categories of crisis management — crisis preparation, crisis response, and crisis recovery.

“Spend what you can but keep the receipts”

-Kristalina Georgieva, Managing Director of the IMF

A country’s response to a crisis will be conditioned by its legal framework, ability to access financial resources, existing rules and procedures, and level of capacity.

The PFM system becomes most stressed during the crisis response stage due to the urgent need to act, reprioritize, and quickly channel resources to priority spending units. Delays can be catastrophic. Consequently, the pressure to respond can supersede established rules and procedures of PFM systems, which is defined as crisis budgeting.

What is Crisis Budgeting?

Definition: A situation in which “budgeting is fundamentally altered, if only temporarily, by pressures that overwhelm established policies and practices”

-Schick, 2009

“Incidental developments, such as the global financial crisis, have affected the realization of the estimates as a number of large investment projects did not materialize.”

-Seychelles

According to Schick, crisis budgeting is a temporary alteration of conventional budgeting due to pressures that overwhelm established policies and practices. It is characterized by special procedures, improvisations that redistribute budgetary power, and significant changes in revenue or spending outcomes. Crisis budgeting is a recognition that the PFM policies and practices established for ‘normal times’ may be too rigid and impractical during a crisis. Instead, greater flexibility and adaptability are required, both on the revenue and expenditure sides.

Urgent revenue mobilization is often needed to finance the crisis response. There are two main sources of crisis revenue:

external revenue

The government receives grants, loans, and other funding.

internal revenue

The government issues domestic debt, such as treasury bills, bonds, notes, and government stocks.

Disaster risk Insurance is another source of revenue. For example, the World Bank offers a Catastrophe Deferred Drawdown Option (CAT DDO), which is a contingent financing line that provides immediate liquidity to countries to address shocks associated with natural disasters and/or health-related events.

As governments take on this additional revenue, it is likely to influence their debt management strategy. During a crisis, expenditures typically rise while revenue typically falls, leading to larger fiscal deficits than anticipated. Therefore, additional revenue is often needed to help finance the crisis response, which may also include tax relief actions and other economic and social measures. Debt service payments, however, should be safeguarded to avoid a potential default, which would further exacerbate the crisis. It may thus be necessary to make suitable adjustments to the annual borrowing program and issuance calendar and/or to take other measures to ensure debt management is aligned with the government’s policy objectives.

Learn more about budgeting during a crisis from these two special series documents by the IMF: Budgeting in a Crisis: Guidance for Preparing the 2021 Budget and COVID-19 Funds in Response to the Pandemic

The request for additional funds by Ministries and Departments that fundamentally alter the allocation of expending in the course of the year.

The movement of budgetary resources between line ministries, programs, policy areas, expenditure categories, or line items. Virements (a) take place after the budget has been authorized by the legislature, (b) do not affect the total level of budgeted expenditure, (c) should not fundamentally alter the composition of expenditure appropriated by the legislature, and (d) are carried out under the executive authority of the government and do not require legislative authorization.

General government transactions, often with separate banking and institutional arrangements that are not included in the annual state (federal) budget law and the budgets of subnational levels of government.

A contingency reserve is a pool of resources within the annual budget that can be used to adapt the budget to changing circumstances or emergencies.

Dimension 21.4 of the PEFA framework assesses the frequency and transparency of in-year adjustments to budget allocations. The dimension recognizes that governments may need to make in-year adjustments to allocations in the light of unanticipated events that affect revenues or expenditures.

Most of these crisis budgeting tools are discouraged during normal budgeting times.

Many budgeting processes have evolved to discourage flexibility and adjustments, which can lead to higher risks of fraud and misappropriation. During a crisis, however, the rigidity of established rules and procedures can inhibit the government’s ability to respond. With the added flexibility of crisis budgeting tools, priority spending can be accelerated to ensure government action benefits those in need.

A crisis, however, creates new opportunities for integrity violations. As controls are relaxed to urgently spend funds, there are increased risks for fraud and corruption in public procurement and stimulus packages and within public organizations. For example, during the COVID-19 crisis, there were cases of contracts being awarded to dubious companies, price gouging on key equipment and supplies, and many other instances of fraud (see, for example, OECD 2020).

“Achieving the appropriate balance between flexibility and accountability is more important than ever.”

As funds are rapidly disbursed to the front lines, governments need to ensure that their PFM systems can effectively track and guarantee the efficient use of resources. The following additional PFM measures are critical to effective crisis governance.

“Once the crisis ends, it is essential that budgeting reverts to pre-set routines, stable roles, and predictable outcomes. An important consideration is deciding what the “new normal” will be in the post-crisis phase. Ideally, lessons from the crisis should motivate reforms that strengthen the resilience of PFM in preparation for the next crisis. Typically, the crisis and its aftermath will spur governments to pay greater attention to fiscal sustainability, the means to assess fiscal risk, and reforms that integrate risk estimates into the budget and other financial statements”.

-Schick, 2009

ADDITIONAL PFM MEASURES THAT HELP COUNTRIES MANAGE CRISES

Advance preparedness for emergency procurement is essential to crisis response and management. Governments can take steps before a crisis occurs to optimize the response capacity of procurement systems, including by:

- Integrating procurement considerations into crisis response plans.

- Developing emergency procurement procedures and tools.

- Allocating budget for emergency procurement facilities.

- Ensuring readiness for supplier mobilization.

Maintaining fiscal transparency is crucial for ensuring public accountability to crisis response. Measures that focus on promoting enhanced reporting on crisis-related spending are likely to safeguard transparency during crises, including by:

- Preparing financial statements (within the current basis of accounting - cash or accrual) to provide a comprehensive overview of the impact of crisis.

- Issuing interim financial statements to enable timely decision making by policy makers.

- Issuing financial statement analysis and explaining the impact of the crisis on public finances.

Efficient cash management is crucial to crisis response. Measures that support timely treasury operations during crises include:

- Developing instructions for interim emergency treasury operations.

- Reviewing and consolidating idle cash into the consolidated fund.

- Enhancing fiduciary oversight and reporting mechanisms.

- Strengthening information technology security and infrastructure, including system capabilities.

Timely ex-post audits are vital to ensuring that governments are answerable for their correct use of public funds when responding to crises. Steps that can safeguard public accountability include:

- Securing audit trails through monitoring, documenting and analyzing government responses.

- Maintaining effect communication with key stakeholders.

- Conducting real-time audits to provide timely feedback to the executive.

- Planning compliance, financial, and performance audits of the government’s crisis response.

Early Trends from the Response to COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic affected every single country. The speed and extent of spread was unprecedented in the modern era. With nearly 500 million confirmed cases, more than 6 million confirmed deaths, the social impact was severe, which in turn affected every aspect of business and socio-economic development. When the first human case of COVID-19 was identified in December 2019, no one could have predicted the devastating impact that COVID would have on lives, livelihoods, and the planet.

COVID-19 Timeline

2019

December

First human cases of COVID-19 are identified in Wuhan, People's Republic of China.

2020

January 30

The World Health Organization (WHO) declares the COVID-19 outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern.

2020

March 11

The WHO declares the COVID-19 outbreak a Global Pandemic.

2020

April 2

1 million cases across 171 countries, with at least 51,000 deaths.

2020

September 19

1 million recorded deaths.

2020

October 11

1 million recorded cases in just three days.

2020

November 7

50 million recorded cases.

2020

December 8

First COVID-19 vaccination is administered in the United Kingdom.

2021

January 25

100 million recorded cases.

2021

July 16

10% of the world’s population is fully vaccinated.

2021

August 26

25% of the world’s population is fully vaccinated.

2021

November 1

5 million recorded deaths.

2022

January 6

50% of the world’s population is fully vaccinated.

2022

April 12

500 million recorded cases.

2022

May 13

60% of the world’s population is fully vaccinated.

36

... of 49 African countries (73%) surveyed used a supplementary budget tool to respond to COVID-19.

Supplementary budgets were a commonly used tool to respond to the crisis. According to the public finance survey of African countries carried out by the Collaborative Africa Budget Reform Initiative, 36 out of 49 countries used a supplementary budget tool to respond to COVID-19. The overall budget envelope increased in 25 cases and decreased in 11.

Notes: The table records budget increases as a result of supplementary budget laws (SBL) adopted after March 1, 2020 and excludes SBL adopted after December 2020. Source: CABRI 2021