What Is PEFA?

This section introduces the Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability (PEFA) program and methodology. It describes what PEFA partnership is, how PEFA measures public financial management (PFM) performance, as well as the advantages and limitations of the PEFA data.

The PEFA Partnership Program

PEFA is a partnership program of the European Commission, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, and the governments of France, Luxembourg, Norway, the Slovak Republic, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. The partnership was set up to establish a uniform approach to collecting information on countries’ public financial management performance.

The PEFA framework identifies 94 characteristics (known as dimensions) within 31 key components of PFM (known as indicators) in seven broad areas of PFM (known as pillars).

The PEFA Framework

The PEFA program provides a framework for assessing and reporting on the strengths and weaknesses of PFM using a letter-grade scoring system to measure performance. PEFA is designed to provide a snapshot of PFM performance at a specific point in time. The methodology can be replicated in successive assessments to document changes in performance over time.

"The PEFA program provides a framework for assessing and reporting on the strengths and weaknesses of PFM."

PFM in instrumental in the achievement of broader development objectives: macroeconomic stability, efficient resource allocation, and service delivery. Good PFM is “the linchpin that ties together available resources, delivery of services, and achievement of government policy objectives. If it is done well, PFM ensures that revenue is collected efficiently and used appropriately and sustainably” (PEFA Secretariat 2016).

PEFA Explainer Video

The PEFA framework identifies 94 characteristics (known as dimensions) within 31 key components of PFM (known as indicators) in seven broad areas of PFM (known as pillars).

PEFA 2016 Framework

The updated PEFA framework was launched in 2016 (often titled PEFA 2016) and is based on the stages of the annual budget cycle. It recognizes that a good PFM system is instrumental in supporting the objectives of aggregate fiscal discipline, strategic allocation of resources, and efficient delivery of services. The framework can be applied at both national and subnational levels.

"The updated PEFA framework is based on the stages of the annual budget cycle."

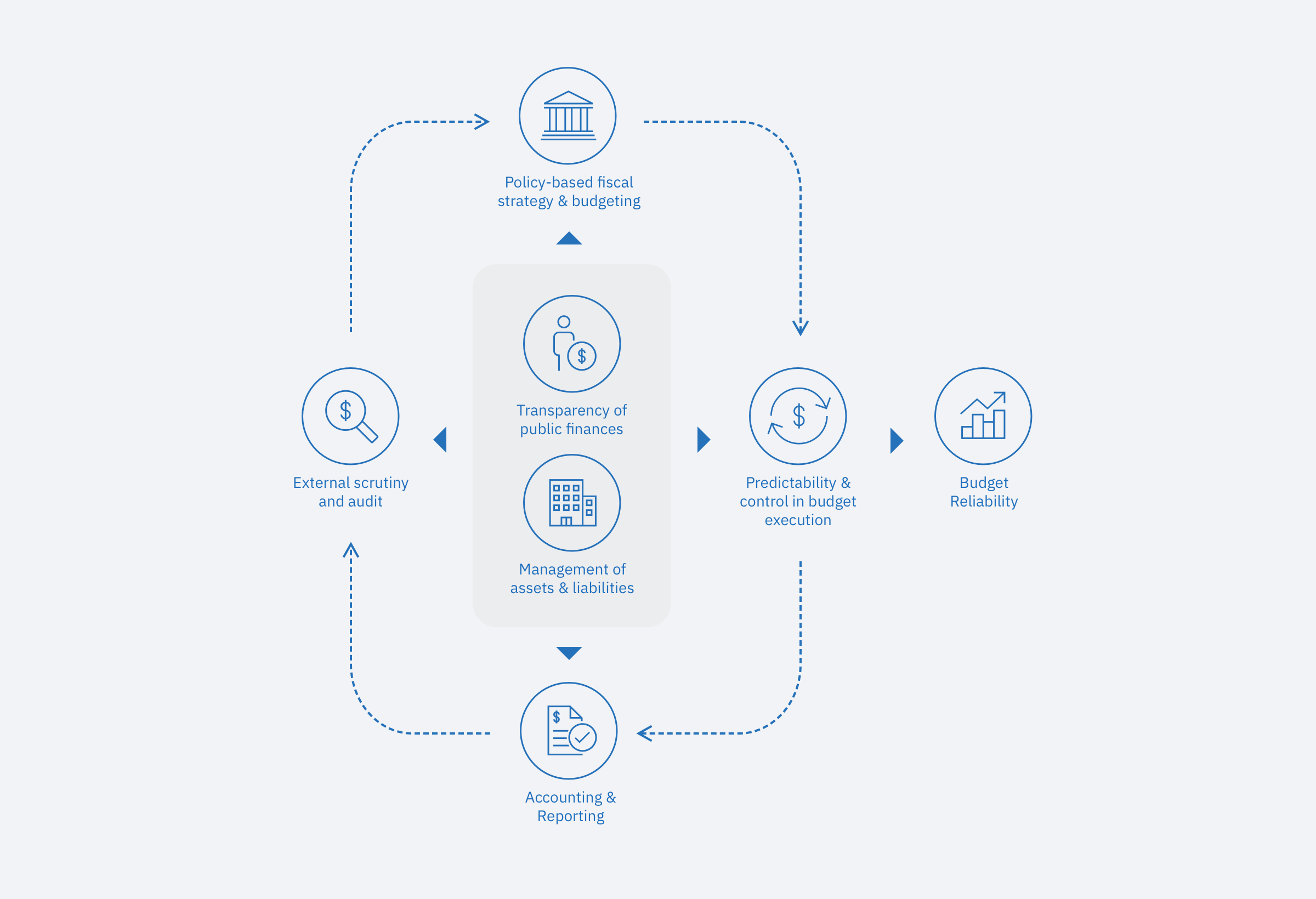

The figure illustrates the PFM system as outlined in the PEFA 2016 framework. It includes seven pillars corresponding to the phases of the budget cycle—policy-based fiscal strategy and budgeting, predictability and control in budget execution, accounting and reporting, and external scrutiny and audit. It also includes two cross-cutting pillars on the transparency of public finances and the management of assets and liabilities and a pillar on budget reliability that represents an output of the budget process.

The PFM system according to the 2016 PEFA framework

Source: PEFA Secretariat 2016. Note: PFM = public financial management. PEFA = public expenditure and financial accountability.

Pillars

Framework 2016 Stats

The table below presents the 7 pillars, 31 indicators, and 94 dimensions of the PEFA framework.

More information on the PEFA 2016 methodology is available on the FAQ section of the PEFA website or in the 10 Things about PEFA 2016 leaflet.

The 2016 PEFA framework indicators

Want to know more about the previous 2011 version of the framework and its indicators set?

Previous Versions of the PEFA Methodology

The PEFA methodology has evolved over time. First released in 2005, updated frameworks followed in 2011 and 2016. Unlike the 2016 framework, the 2011 framework did not represent a significant departure from the 2005 framework, as only three indicators were revised (PI–2, PI–3, and PI–19).

Using PEFA to Measure Changes in Performance over Time

The 2016 framework represents a significant revision from previous versions. While some indicators remain directly comparable, other indicators have been revised, dropped, or added, rendering them less comparable or, in some cases, incomparable.

The transition to the 2016 framework has been managed by the continued use of the 2011 framework in an accompanying annex. This dual assessment approach generated one more wave of comparable assessments within the data set, creating a larger sample of comparable indicators with which to observe changes in PFM performance over time.

A high-level overview of how PEFA indicators and dimensions of 2016 and 2011 methodologies are connected and a more thorough analysis of similarities and differences between the two frameworks are available at the resources section of the PEFA website.

How PEFA Measures PFM Performance?

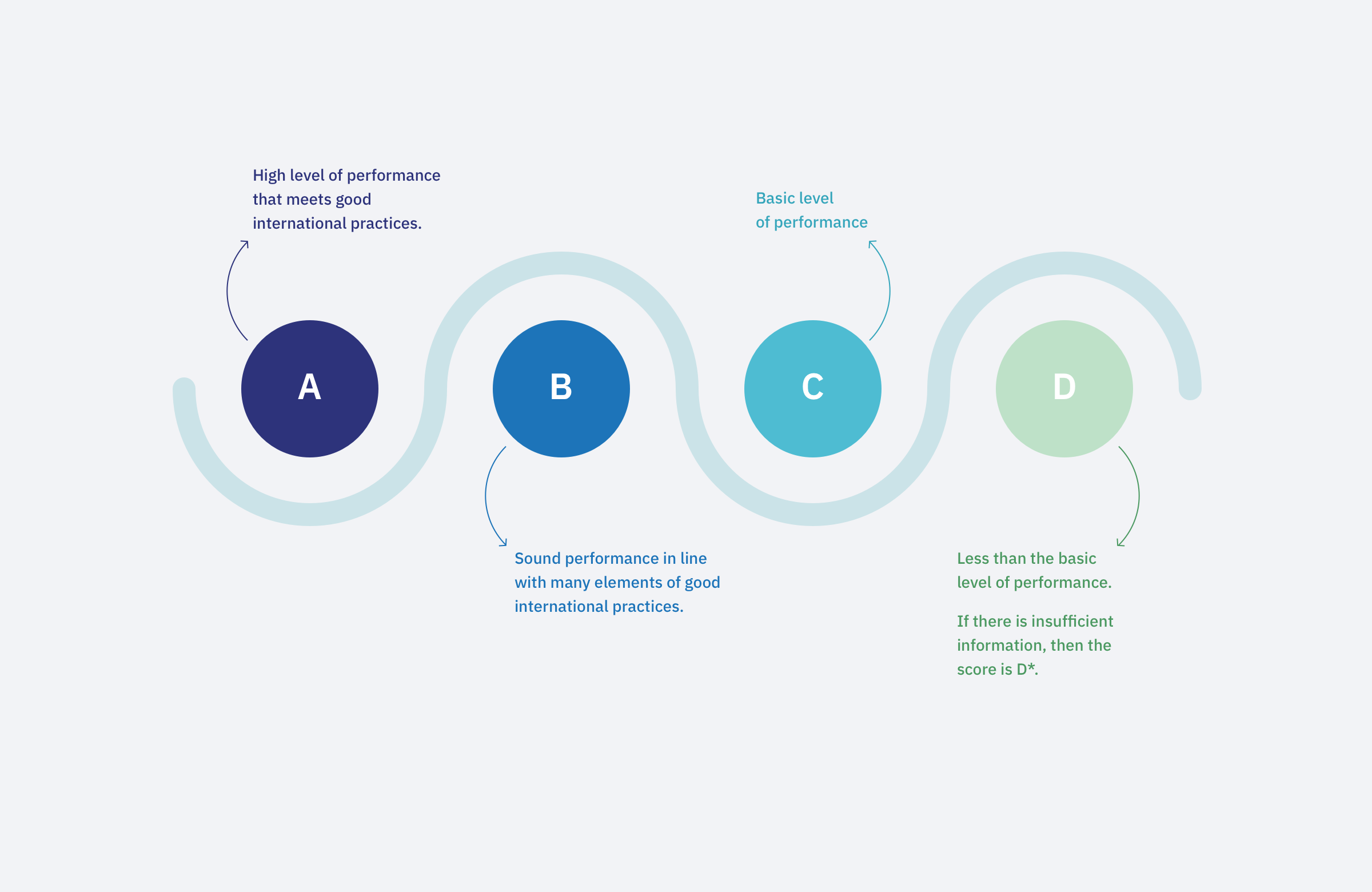

Each dimension measures performance against a four-point ordinal scale from D to A that captures levels of compliance with good practices in PFM. D is the lowest score; A is the highest score.

Scoring the PEFA indicators

Note: PEFA = public expenditure and financial accountability.

Methods

To calculate the indicator score, the assessor must combine the dimension scores using one of two methods referred to as method 1 (M1) and method 2 (M2). The scoring method is clearly prescribed for each of the indicators.

Objectives

Performance indicators with only one dimension simply take the score of this dimension and are not eligible for a “+“ rating.

A score rated as NA (not applicable) is used when a dimension or indicator is not applicable to country circumstances (for example, the assessment of fiscal risks stemming from subnational governments is not applicable for small countries with no subnational governments). In the 2016 framework a score rated as D* replaced a score of NR in the previous version of the framework for cases where information to score a dimension is lacking (lack of information is not considered good practice).

Advantages and Limitations of PEFA

The PEFA framework emerged in 2005 as the instrument that harmonized various PFM diagnostic tools used by development partners. As a result, it has become the most widely used assessment of PFM performance.

Advantages

Limitations

References

Andrews, M. 2009. “Isomorphism and the Limits to African Public Financial Management Reform.” HKS Faculty Research Working Paper RWP09-012, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. https://dash.harvard.edu/handle/1/4415942.

Andrews, M. 2011. “Which Organizational Attributes Are Amenable to External Reform? An Empirical Study of African Public Financial Management.” International Public Management Journal 14 (2): 131–56. doi: 10.1080/10967494.2011.588588. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10967494.2011.588588

PEFA (Public Expenditure and Financial Acountability) Secretariat. 2016. PEFA 2016 Framework. Washington, DC: PEFA Secretariat. http://pefa.org/resources/pefa-2016-framework.